At http://anthropology.net/2014/02/07/oldest-hominin-footprints-found-outsi… … is a report on the discovery of human footprints at Happisburg in Norfolk, going back, it is believed, to 850,000 years ago.  Ther research was headed by Nick Ashton of the British Museum. This is probably not the best site to read this story so see also www.archaeology.co.uk/articles/features/colonising-britain-one-million-y… which is the web site of Current Archaeology and the article is right out of the current issue (Feb/March 2014). This can be purchased at WH Smith nowadays – worth the pennies.

Ther research was headed by Nick Ashton of the British Museum. This is probably not the best site to read this story so see also www.archaeology.co.uk/articles/features/colonising-britain-one-million-y… which is the web site of Current Archaeology and the article is right out of the current issue (Feb/March 2014). This can be purchased at WH Smith nowadays – worth the pennies.

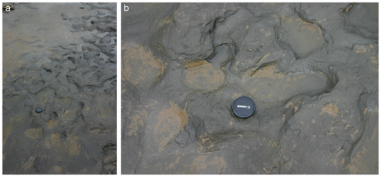

The footrpints, above, belong to both children and adults, captured for posterity – or perhaps not. They were subsequently washed away by the tide.

At British Archaeology of September 2010 there was another article on Happisburg. It all began with the discovery of a beautiful black flint tool by a man taking his dog for a walk. it was half sticking out of the cliff face – there had recently been a collapse of material. At Happisburgh a submerged forest was uncovered (reported on In the News two years ago). Tree roots could clearly be seen on the beach.

The story at Current Archaeology (above link) 288 has the headline One Million years (which says the footprints are 900,000 years of age. The headline is also the title of an exhibition at the Natural History Museum, beginning on February 23rd (and going on until September). The discovery was found beneath cliffs composed of sand, gravels, and silt (or mud) that indicates an estuary situation, on a bay of the sea. Britain was still joined to Europe at that time so this interpretation is not definite, although they are thinking in terms of the southern basin of the North Sea being dry land and the northern basin of the North Sea being open water.

The story begins in the 19th century when fishermen brought up teeth, bones and horns of extinct animals, off the Norfolk coast. In 1825 a high February tide swept away large sections of the cliffs and exposed fossil peat, fir cones, animal bones, and tree stumps. The prehistoric landscape is thought to stretch 50 miles under the sea – and it became geologically known as the Cromer Forest Bed. In 1877 another tidal surge together with a storm caused large heaps of ironstone to be washed up on the Happisburgh beach. These were covered with the impression of leaves from oak, beech, elm. birch and willow. This tweeked the fancy of Clement Reid, a palaeobotanist, and using a boat and a grab hook he wet out to sea to collect further examples. The realisation that Britain had once been joined to the continent slowly sank in.

Palaeolithic tools are found across much of Britain but the physical remains of the people that made them are few and far between. Fragments of human bone have been found at Swanscombe in Kent, at Pontnewydd in N Wales, Kents Cavern in Devon, Gough's Cave in Somerset and Boxgrove in Surrey. Pakefield near Lowestoft in Suffolk became famous fr ht e stone tools that came out of the cliff (see above) and for stratified deposits tha also contain fossil animals and fossil plant material. The finds indicate a Mediterranean climate – at 700,000 years ago. In contrast, the Happsiburgh footprints at 900,000 years ago are said to resemble the sort of flora that exists in southern Scandinavia in the modern world. So, we have what look like two Interglacial episodes. Unfortunately, geology does not recognise catastrophism as a factor in the laying down of sedimentary material, even when it consists of mud, sand and gravels.

Next on the research horizon is the bottom of the N Sea. Doggerland is soon to be explored – but how much damage has been done by the offshire whirlygigs? The Dogger Bank is thought to have been an island until 5000BC. This opinion is an estimate driven by uniformitarian rates of sea level rise – and does not take into account periodic catastrophes that may have caused sudden and unpredictable rises in sea level. In other words, sea level rise by spurts and lulls, rather than a continuous and gradual process. We don't know when the island of the Dogger Bank was submerged. It could have been just a few thousand years ago.

Sites such as Pakesfield and Happisburgh are too early for effective use of C14 dating methodology. Anything older than 40,000 years ago is subject to error and considered unrealiable. How much this has to do with a massive C14 plataeu at the time is unclear but it is notable that this date coincides with a major Pleistocene extinction event, which decimated large numbers of mammals of all kinds. It also happens to coincide with th disappearance of the Neanderthals, and the subsequent appearance of modern humans. Is there a connection – and is that connection due to a catastrophic event (or events).

The Anglian ice sheet is thought to have altered much of the geology of Norfolk around 450,000 years ago – and you can see huge blocks of chalk that have either been pushed by glaciers or by water (in a catastrophic manner). So, the geology is used to date strata – and not C14. Plants and animals also give a clue to dates – or the sequence of events. Animals change over time and the lowly vole is one such animal that has proved useful in this respect. Modern voles have teeth that keep on growing but early voles had teeth with fixed roots. At Pakesfield the voles were the latter. It's a fascinating subject – and some very clever work has been done. Dates don't really matter in the grand scheme of things (900,000 years or 100,000 years are pretty meaningless terms). However, the passage of time is important for the gradualists – the uniformitarian hypothesis which is the consensus lynch pin of all things older than last year. Therefore, should we just shrug our shoulders and go along with the flow – or should we point out there is another way of looking at things. Are the footprints really 900,000 years of age?