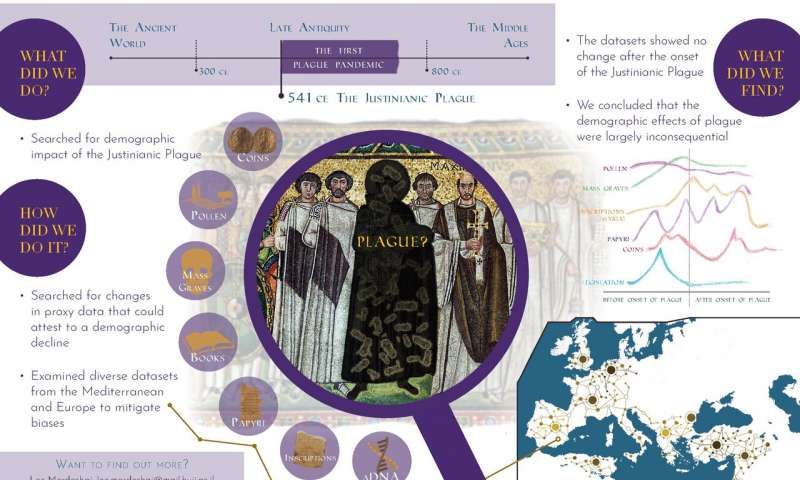

At https://phys.org/news/2019-12-justinianic-plague-landmark-pandemic.html … which is derived from https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1903797116 … a new study shows the historicity of the Justinian pandemic is inconsistent with facts on the ground. That is the claim. It comes courtesy of sociology and environmentalism (a combination of some kind) at the University of Maryland, with others from Princetown's 'Climate Change and History Research Initiative' department. Basically, they are disputing the notion that an outbreak of Bubonic Plague during the reign of Justinian drastically reduced the population of Europe. They futher claim that historians do not have the full picture – and as environmentalists they are able to look at other fields (as if historians were unable to do the same thing). The claim is that populations across the Mediterranean basin and the Levant were not decimated by plague (or presumably by any other factor as they seem to be saying population numbers were not diminished). They looked at data between AD300 and 800, examining contemporay written sources, inscriptions, coinage, papyrus documents, pollen samples, plague genomes and mortuary archaeology (burials). Mainstream historians are said to be obsessed by some documents which do mention the plague and ignore others which do not mention it (over the same period of time). This is interesting as it might suggest the plague outbreak was localised rather than a global manifestation. It was recently revealed that bubonic plague outbreaks occurred in around 3000BC and 2500BC – brought into Europe by invaders from the steppe zone. Justianian was involved in a major war with the intention of restoring the Roman empire in the west, fighting a protracted campaign against the Goths (who also had a steppe origin), and the Avars (with a more distant steppe origin). As far as we know the Goths and Avars did not penetrate as far as the Levant so perhaps they have discovered an important aspect of history – but time will tell as historians are bound to bite back.

… The argument is that historians have greatly exaggerated the severity of the Justinian Plague (even though it brought an end to ambitions to recreate the Roman Empire for a couple of centuries and led to the establishment of Gothic and other barbarian kingdoms across western Europe). It was nowhere near as severe as bubonic plague in the 14th century AD which really did reduce populations across Europe and western Asia. That is the thrust of the article in PNAS. Pollen evidence, for example, is said to show that agriculture continued in an interrupted manner – which appears to be one of their major data points. It sounds a bit like the evidence from pollen analysis in Britain which seems to show there was no reversion to scrub or the wild wood and farms continued to operate (right through the 5th and 6th centuries AD). At the same time we know that several million people lived in Britain during the Roman period but no more than a million in the centuries that followed. Or do we? Is that another cat among the pigeons.

… The argument is that historians have greatly exaggerated the severity of the Justinian Plague (even though it brought an end to ambitions to recreate the Roman Empire for a couple of centuries and led to the establishment of Gothic and other barbarian kingdoms across western Europe). It was nowhere near as severe as bubonic plague in the 14th century AD which really did reduce populations across Europe and western Asia. That is the thrust of the article in PNAS. Pollen evidence, for example, is said to show that agriculture continued in an interrupted manner – which appears to be one of their major data points. It sounds a bit like the evidence from pollen analysis in Britain which seems to show there was no reversion to scrub or the wild wood and farms continued to operate (right through the 5th and 6th centuries AD). At the same time we know that several million people lived in Britain during the Roman period but no more than a million in the centuries that followed. Or do we? Is that another cat among the pigeons.

Historians may well have been too eager to think in terms of a drastic collapse in population but in British sources it was a yellow cloud (in the atmosphere) that was blamed rather than a pandemic as such. In other words, death may have come as a result of an Icelandic volcano or the noxious cloud was left behind after the passage of Comet Halley (just prior to the date assigned to the plague). Meanwhile, some historians have already jumped on the climate change bandwagon pointing to a sudden cold blimp in the 540s AD. The full article can be read at the link above.